Whosoever increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.

Book of Ecclesiastes, 1.18.

London’s Natural History Museum in South Kensington retains an extensive archive of unincorporated and unidentified species in its vast holdings. To give an idea of the scale of the institutional backlog the sheer number of holdings create, it is estimated that working at the current rate, it would take archivists at least twenty-five years to catalogue just the museum’s holdings of unknown gastropods. Considering this situation, the artist Mari Bastashevski, herself engaged in an in depth research-based project with snails and other gastropods entitled Unwhorl, has observed that in the time it would take to professionally catalogue all these species, many of them would likely be extinct. The profound melancholia of the archive is revealed in harsh relief in such a circumstance: knowledge comes too late to be actionable. Order and entropy weave past each other, and the archivist is left with the hollowest of victories: a kind of negative certainty; something was, but such knowledge is little more than tautology: to know is only to know. The case of the Natural History Museum’s collection of gastropods (gastropods making up the largest group within the biological phyllum Mollusca) is just one example of the dilemmas that archives, and the institutions that house them, face in a moment of profound structural change.

To preserve something requires energy but often the energy dedicated to preservation of records usurps the preservation of the subject of the research. Knowledge about the climate crisis is acquired often through manifestations of it. Knowledge of the consequences of systemic racism and other forms of discrimination are entering history, but is this knowledge enough to consign structural discrimination to history? Cultural institutions are filled with booty from the plunder of territories and cultures, as the belated reckoning with cultural theft Germany and other European countries are experiencing demonstrates. These artefacts have served as bearers of knowledge but it is a knowledge that has been enclosed by specialists in colonial metropoles and only impoverished the cultures that produced the works themselves. The grotesque realities of European and American museums facing the moral burden of returning human remains to their rightful places is a particularly egregious expression of the brutality of the archiving process.

Democratising the repositories of knowledge

Finally, the blood-price paid for archives of medical knowledge is increasingly becoming well known, from the Mengele experiments in wartime concentration camps, to the monstrous Tuskegee Experiment in the US state of Alabama, in which Black men with syphilis who came seeking treatment as part of a US Public Health Service initiative were left untreated over a period spanning decades to determine the effects of the advancing disease and withheld treatment.

Medical records also document the depredations of the “father of modern gynaecology” J. Marion Sims, and, of course, a litany of iconic psychology experiments involving coercion and manipulation, as well as the contemporary use of animal testing in cosmetics and other products. Every fact derived from these interventions was purchased with a cry of pain. Medicine and biology, however, are only the most extreme expression of the ways in which the violence and exclusion of the gathering, cataloguing, and preservation of knowledge are revealed. Institutions derived from colonial cultures all have their own signature practices of archiving and sequestering knowledge among ‘experts’. In the light of the risibly inadequate address of these loci of power to the interlocking crises facing humanity, the imperative to demoractise repositories of knowledge is overwhelming. The question humanity faces is how (and whether) this need will be met despite the prerogatives of power.

Archives perhaps have an unduly staid reputation. The first image one may think of to associate with the term “archive” is that of a library, or some other academic institution, perhaps this space is somewhat clinical, perhaps it is covered in dust, often, it is seen as being separated from the dynamic world beyond the walls in which it is housed. The emergence of the data economy over recent years, however, demands a new vision of what it means to conceptualise an archive. Perhaps the most powerful archive of all, at the present moment, is the mobile device so many people carry with them in their pockets, methodically recording their every move and location, often their purchases, sometimes even their conversations. These archives are vastly more distributed than their brick and mortar predecessors, but they are equally inscribed with the same kind of power asymmetries and moral indifference. The archives created by smartphones and internet-of-things devices are infinitely distributable, constantly in flux, and, as the Harvard scholar and cultural philosopher Shoshana Zuboff notes in her 2019 book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, they are capable of capturing and archiving information users are not even aware that they are creating (a person may know they visited multiple websites, they may not know exactly how long they visited them, or how many saccades their eyes produced while viewing them). As in the case of the victims of earlier archives, the users of smart devices have little or no control over how the information they produce is recorded and instrumentalised.

"The emergence of the data economy over recent years, however, demands a new vision of what it means to conceptualise an archive."

The intrinsic repression inscribed within this information asymmetry is compounded by the hyper-awareness the main clients of these archives have of about the information recorded. Not only do the platform companies, their clients and the governments that collude with them have agendas for the data they gather, there is an entire industry concerned with making the searching of this archive easier and more efficient. Data brokers who work with commercial clients, and companies like Peter Thiel’s Palantir, which specialises in the analysis and organisation of huge data flows, explicitly understand the value they extract from archives they can access (for a price), and then repackage and sell on ad infinitum. The archive may be increasingly dematerialised, but it is no more democratic for being so. The ends entities like Palantir serve are as alien to the needs of most of humanity as the ends of the Natural History Museum are to the gastropods in their archive.

The archive is open, and it is hungry.

The dematerialisation of archives and the embrace of the notion of a dynamic archive has become something like a default expectation in digital culture. Perhaps nowhere is this more robustly expressed as in the cultures that have emerged around crypto currencies and the blockchain ledger that supports their mining and exchange. Crypto enthusiasts take many forms. From ecstatic libertarians positioning crypto currencies as the engine of a future ungoverned, hyper-individualised humanity, to the more staid - if perhaps equally over-optimistic - founders of the think-tank Blockchain For Good who see the distributed ledger technology as a means for strengthening rather than eliminating institutions. The blockchain is itself an archive, of course, purporting to offer users a record of every transaction that has occurred involving it. The archive is fully accessible to users from its first moment of existence to the most recent transaction carried out within it. Such (ostensibly) perfect knowledge represents a tremendously attractive proposition in the world of finance where transactions are often murky by design. Clarity itself is a kind of commodity in the practice of archiving - as Thiel and company understand. The techno-utopian vision is surprisingly prominent even in an age of corporate and government surveillance overreach. It posits that blockchain will make it possible to create new systems of exchange, knowledge, and cultural production. Individuals and communities will be liberated from the oppressive information asymmetries that characterise the current state of data capture and enclosure by platform companies. Everyone in the world of blockchain plays on a level informational playing field, the archive is open and it belongs to everyone who makes use of it. But as the blockchain’s most famous resident, Bitcoin, increasingly is proving, even when an archive is transparent, it may not be democratic, let alone beneficial. At the heart of the problem with Bitcoin and blockchain are their exorbitant use of energy. Research by The Netherlands’ Central Bank - admittedly an institution unlikely to be favourably disposed to crypto-currencies - estimates that as of 2021, Bitcoin alone is responsible for CO2 emissions of more than twenty times the entire global electronic card payment system. Attempts to make crypto greener has, at best, only proven marginally successful. All the while the entropy engine that is Bitcoin surpasses entire nation states in its annual energy consumption. The archive is open, and it is hungry.

The advance of what might be called “crypto mindset” is growing like Bitcoin’s energy appetite. Recently, bubbles have begun inflating around an epiphenomenon of the blockchain, the non-fungible token or NFT. NFTs have often been used as means of image production, often involving sporting clips, and tradeable digital character images including the (now very expensive) CryptoPunks. But now that fine art audiences are discovering them at scale, they have morphed into a kind of (financial) instrument of institutional critique, set to offer artists and other cultural producers ways to escape the inequalities embedded in the existing art market.

The gatekeeping role of museums has long been a target of artists and critics. The status of the museum as a kind of cultural archive and repository of aesthetic knowledge has long been contested. Indeed, as the critic Douglas Crimp, a leading voice in the modern iteration of institutional critique noted in his influential 1980s essay, On the Museum’s Ruins: “founded on the disciplines of archaeology and natural history, both inherited from the classical age, the museum was a discredited institution from its very inception.” Crimp cites Gustave Flaubert in support of his argument: “The set of objects the Museum (sic) displays is sustained only by the fiction that they somehow constitute a coherent representational universe”. Crimp is arguing against a very specific notion of the museum as an institution, one that is concerned with its status as a site of “knowledge”, but the advance of technology is also at the heart of Crimp’s critique. He argues, too, against the French novelist André Malraux’s, rather reductive analysis of the future of the museological archive in his work The Museum without Walls, published during his tenure at the Ministry of Culture in the administration of Charles de Gaulle. Malraux was fascinated by the way photography and other technological means of image distribution were changing the archival character of the museum. In an age of easily reproduced photographs, and widely available mass circulation cultural publications, the works immured within physical museums truly come to life outside it. This is perhaps a convenient position for a man once arrested by the French colonial authority - an institution not known for its sensitivity to indigenous sensibilities - for the theft (or “liberation” to use Malraux’s term) a bas relief from the Banteay Srei temple in Cambodia.

To whom does the museum belong?

In our age of infinite image distribution, the critic David Joselit has offered an updated and more sophisticated variation on Malraux’s (sometimes hands-on) notion of a “distributed museum”. In After Art, Joselit explicitly considers the way art may function as a kind of “currency”. He advocates a “redistribution of image wealth”, a kind of decoupling the value of a visual image from its objecthood. As will be discussed below. However, Joselit’s observation about the flow of images in digital cultural discourse, tragically, has been turned on its head. Instead of devalourising the object, discussion has centred on ways to imbue digital “objects” with the kind of scarcity value Joselit opposes.

Philosopher and art critic Boris Groys approached the question of institutional critique of museums from a different angle. For Groys, the archival function of a museum has been replaced by the advance of the Gesamtkunstwerk manifested institutionally as the “curatorial project”. Groys quotes from Kazimir Malevich’s short 1919 essay On the Museum, in which Malevich notably uses a medical analogy to rail against the preservative character of art museums, “In burning a corpse we obtain one gram of powder: accordingly thousands of graveyards could be accommodated on a single chemist’s shelf”. Malevich and Groys are interested in the museum as a site of production, not merely a place where historical archives are activated, but a locus in which audiences produce artistic meaning immediately. Groys writes, “we begin to understand the museum not as a storage place for artworks, but rather a stage for the flow of art events”. Indeed today’s museum has ceased to be a space for contemplating non-moving things. Rather, the museum is “a place where things happen” where individuals and works interact and emergent cultural experience are the site of significance (as opposed to the surfaces of historical works). Groys attributes this seismic change - along Malrauvean logic - to changes in technology. The internet is what allows the museum to be a place where “things happen”. Things happen in museums, it is true, but most of what is happening when the internet enters a museum takes place outside the walls of the space. In place of a museum without walls, the internet of the museum age is an archive of experience an archive of affect. Anyone who has watched their Instagram feed morph into an infinity of Infinity Rooms whenever there is a Yayoi Kusama exhibition on can attest to the ways in which what is in museums spills over into the wider flood of images and data. The photograph is only a part of the data overspill that the Groysean reimagining of museums’ new status is driven, but given Malraux and Joselit’s interest in the image’s life outside of the museum, and the archival role played by photographs - both printed and (especially) digital, it is useful to return to Crimp’s original skeptical position on the photograph as a “game changer” in the evolution of the museum. Crimp writes: “So long as photography was merely a vehicle by which art objects entered the museum, a certain coherence obtained. But once photography itself enters, an art object among others, heterogeneity is reestablished at the heart of the museum; its pretensions to knowledge are doomed. Even photography cannot hypostatise style from a photograph.” Crimp is certainly correct to highlight the equivocality of the museum as authority or knowledge repository, and his post-modernist interpretation of the slippage of authority created by photographs entering museums as parts of collections is well taken in an online age of what the writer danah boyd has called “context collapse”, nevertheless, perhaps the most fundamental challenge of the authoritative quality of the museum as archive is the problem that was inscribed in the museum at the point of its creation: to whom does the museum belong?

Another archive is built with a prison inside of it

In her 2017 essay ‘Collections Management on the Block Chain: A Return to the Principles of the Museum’, art critic Helen Kaplinsky enters into a dialogue with historical exponents of institutional critique including Crimp, as she considers the role of a new kind of archive that has entered the art world with the advent of the blockchain. Kaplinsky’s essay returns to the origin of the museum in western culture the so-called “Cabinet of Curiosities” that became popular in the Renaissance. These cabinets - again, interestingly often connected to the medical realm and apothecaries, were understood to be sites of knowledge about the world. The connection to the kind of “knowledge” Crimp addresses in his essay may be central to the role of the Cabinets, but Kaplinsky is interested in the way they are a foundation of a culture of visibility. She notes that visibility is a crucial dimension of the creation and design of museums, not merely for exhibitions, but of visitors and spectators themselves. Museums were conceived of as places where people see art, but also see themselves and others seeing art (and see each other seeing each other seeing art) Indeed, Kaplinsky, citing Simone Brown the author of Dark Matters: On The Surveillance of Blackness, notes that the surveillance culture that infuses Zuboffian surveillance capitalism passes through the culture of the museum and exhibition-making. This history provides valuable context for Kaplinsky’s discussion of the distributed ledger technology that is the blockchain. Kaplinsky writes “For both the Victorian exhibition and also the blockchain, the publicness of content (data and exhibited cultural assets) directly serves a recursive process of self governance. Transparency holds to account the fidelity of the internal to the external”. Transparency is only a virtue when power dynamics are clear. The ultra-transparency of the lives of Black people in white societies, as Brown and Kaplinsky note, is the opposite of an empowering proposition. The total data transparency created by the platform economy is not only an engine of further racial oppression, but a broader social pathology that takes in the whole of the global population, rendering their lives transparent and infinitely manipulable to hyper-empowered coteries of elite consumers. The blockchain, with its specialist community, democratises finance only insofar as the societies into which it enters are democratic, otherwise it is a tool of hierarchy. Another archive is built with a prison inside of it.

The status of Blackness within the production, management, and application of archives is an urgent matter, as technological archives and data platforms increasingly define 21st century life. The advance of financial technology firms into formerly colonised Black majority countries is one face of the danger. Such firms have many of the appurtenances of banks without being subject to the (often inadequate) regulatory regimes applied to banks. In their hands, the distributed ledger and the ‘smart contracts’ it licenses, could easily become an instrument of neo-colonialism just as the globally distributed legerdemain of “civilization” was of the original variant of the colonial pathogen. The cultural sphere, despite its highly inclusive rhetoric, has just as often been guilty of accepting the knowledge gained in archives of Black creativity without being so readily accessible to the producers of that cultural capital. Works like the Southern Summer School and the Decolonising Futures project, by the South African artist Simangaliso Sibiya and the Dutch artist Dorine van Meel, take seriously the notion of knowledge production by art institutions, in their specific case, the educational institutions and entities like museums, hoping to locate the present inequalities birthed in colonialist history and perpetuated through the institutions of cultural preservation and memory in coloniser states today. Berlin’s recent reckoning with the legacy of Alexander von Humboldt’s cultural thefts demonstrate that all European institutions must face these questions, these literal skeletons in their closets. The artist Grace Ndiritu began her Healing the Museum project in 2012 with similar aims, to democratise western cultural spaces and foreground a confrontation with histories of theft, repression, and racism in the formation of the “knowledge” produced and preserved by them. Central to Ndiritu’s method was the conscious introduction of what she calls “non-rational healing methodologies” including mediation sessions and what she describes as “shamanism”.

The appearance of certainty

In the near term, as climate breakdown advances and states respond in increasingly desperate ways, certainty, or the appearance of certainty will become an increasingly valuable commodity. Archives like the blockchain may provide an appealing facade of certainty, but as in all the cases discussed above certainty comes at someone’s expense. Data brokers and traders are perfectly happy for the apparent certainty the blockchain attests to become more widely applied; after all, greater certainty about individuals and society make marketing products proportionally easier. The map was the friend of the coloniser in the same way the archive of all social behaviour will be of the data encloser. For an archive more transparent is not fundamentally to make it more democratic. For that to happen the will to interrogate what archives mean, how they are constructed, how they are valued, and who can make use of them. The kind of trans-rational methodologies of Grace Ndiritu may be a starting point, but they are only one. New practices of knowledge recording, sharing, and preservation are a matter of urgency, and one in which everyone can participate. To abdicate this responsibility is a kind of surrender. The certainties we generate will be as useful to us as they will be to the extinct snails in the archive of the Natural History Museum, a record only of our existence and our failure.

Habib William Kherbek

Habib William Kherbek is the writer of the novels Ecology of Secrets, ULTRALIFE, New Adventures, and Best Practices. His short story collection Twenty Terrifying Tales from Our Technofeudal Tomorrow was published in 2021 by Arcadia Missa, and his poetry collection 26 Ideologies for Aspiring Ideologists was published in 2018 by If a Leaf Falls Press. left gallery has published Kherbek's non-fiction monograph Technofeudalism Rising and his video poem collection 'retrodiction'. His journalism has appeared in Block Magazine, Rhizome.org, Berlin Art Link, MAP, Flash Art, Sleek, Port, Samizdat, AQNB and other publications. Abstract Supply will publish Kherbek's collected art writings Entropia: The Childhood of a Critic in 2021.

Mari Bastashevski

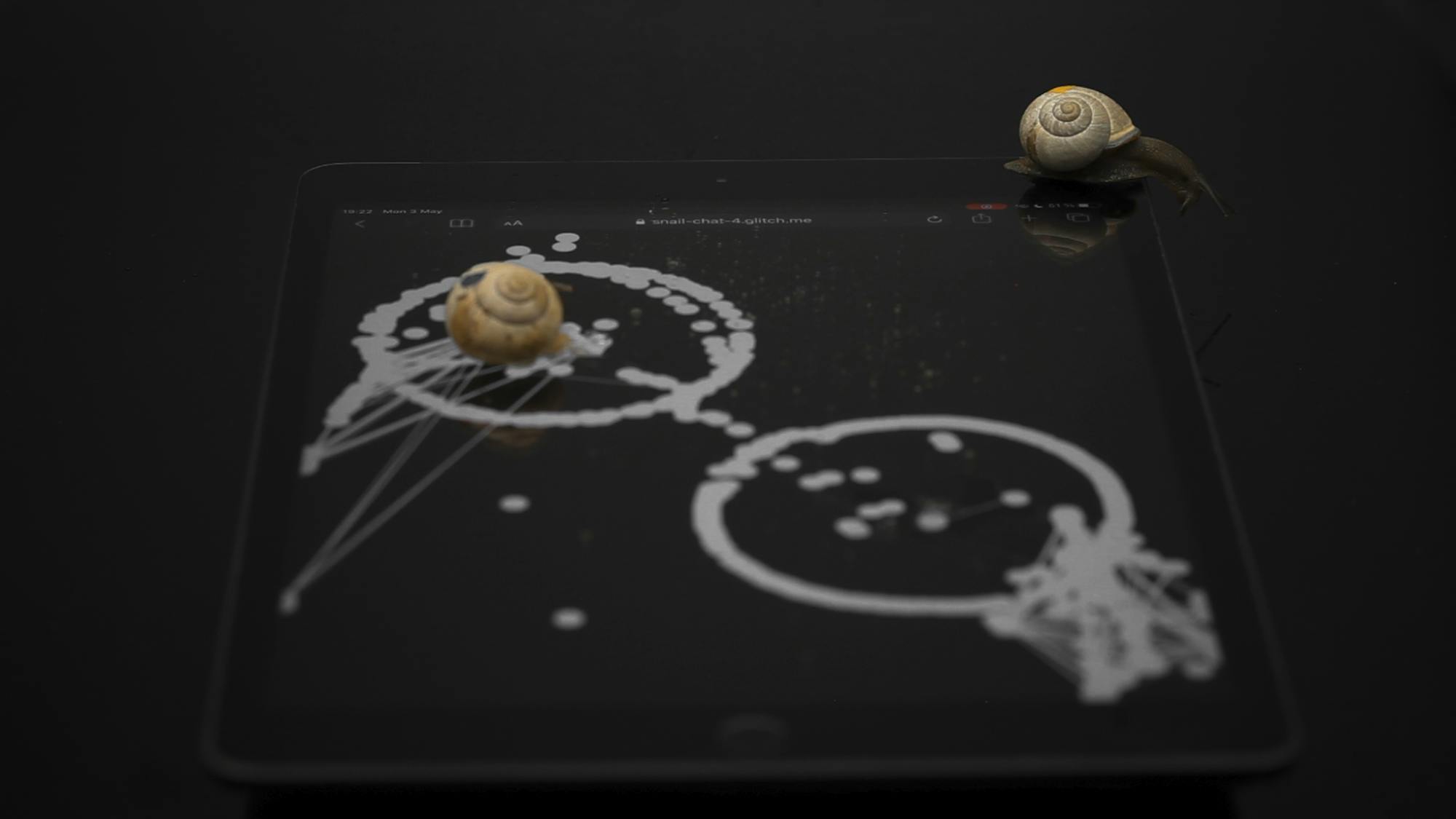

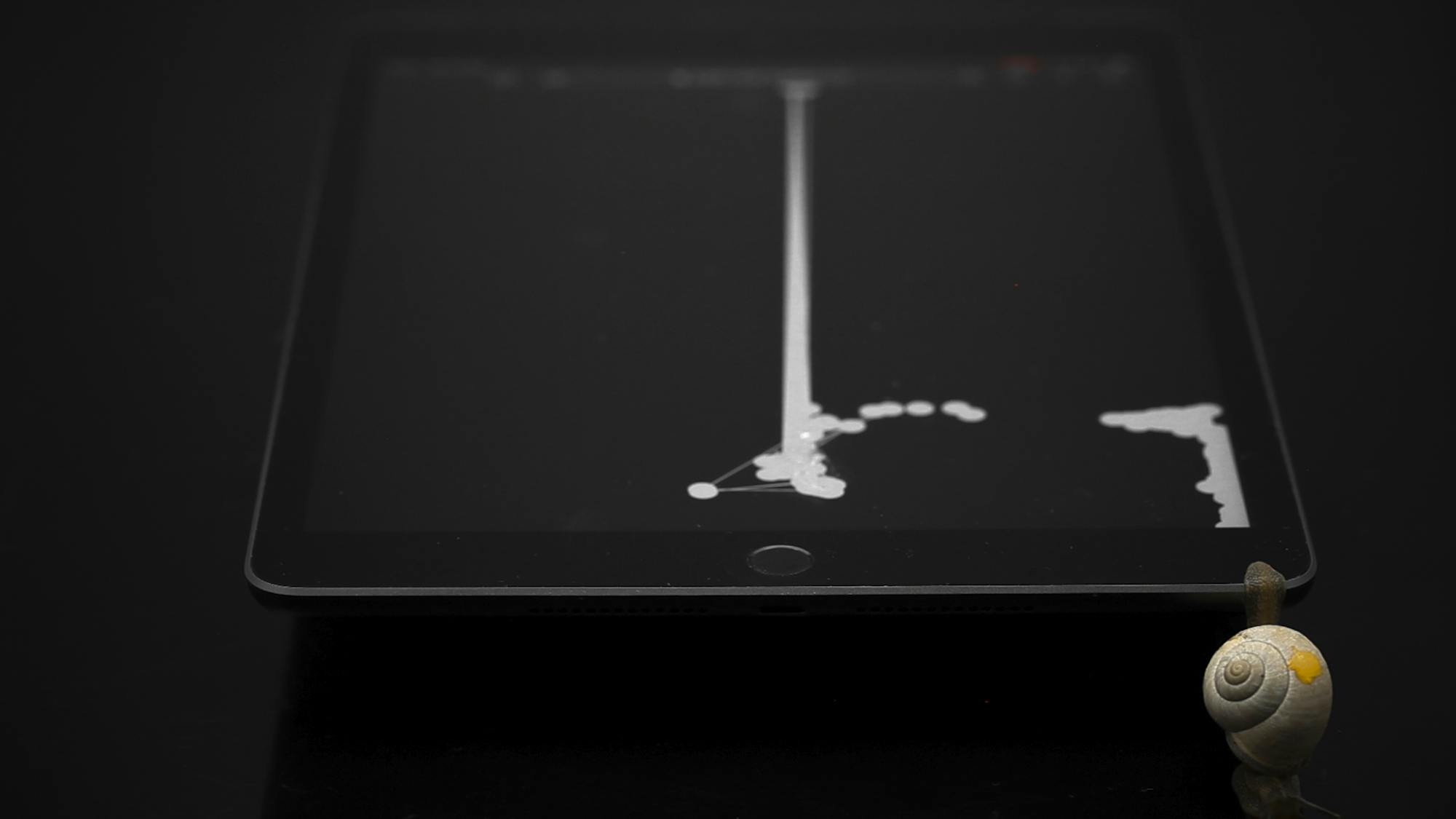

Mari Bastashevski id an artist, PhD at KIT, NTNU, and a visiting scholar at ALICE laboratory, EPFL. Occasionally, she teaches, collaborate across disciplines, and perform random acts of journalism. Unwhorl is a digital interface for snails to communicate in real time between NYC, Berlin, Lausanne, and Rotterdam and part of Bastashevski's ongoing research project Pending Xenophora.