Linnéa Bake and Eva Herrmann on their independent art space soft power.

"soft power is an appropriation of a controversial political sciences term describing the influence 'soft' assets such as culture and art can have on political and economic spheres."

Kemmler Foundation: Could you tell us more about "soft power"? Who are you, since when have you been active, and where does the name come from?

Eva Herrmann: soft power is an independent art space and a curatorial project, co-founded and currently directed by Linnéa Bake and myself, Eva Herrmann. The project started in late 2020 as a collective endeavour, together with our co-founders, artist Donna Volta Newmen and designer Melissa Lücking. Working in the art world, from commercial galleries to institutions or a biennial, had on multiple levels been a disillusioning experience for each of us. I guess our aim was to start an arts organization to do things differently, as disillusioned as that might sound. With our respective backgrounds in curatorial work, social sciences, writing, design and artistic practices, our interdisciplinarily informed understanding of how to tackle established norms and work ethics played a big role in that, and collectivity was our guiding principle, not just between the four of us, but also in terms of how we wanted to work with others.

What happened next?

EH: We successfully applied for a city-funded project space in a former factory building in Berlin-Tempelhof, which motivated us to ask questions about how space is inherently political – from the beginning, it felt important to share the space with others, and to stay critical about the politics and policies of art in its institutionalized forms. In addition to exhibitions and other artistic formats that have been taking place at soft power, as a Kunstverein with a membership structure, we also host changing residencies to make the space accessible to artists, and we frequently invite other curators and initiatives to realise projects in conversation with us and as part of our programming.

Linnéa Bake: Our name, soft power, is an appropriation of a rather controversial term from political sciences that describes and uses the influence which “soft” assets such as culture and art can have on political and economic spheres. In our ongoing collaboration, we are working on critically examining the term “soft power” as a conceptual framework through curatorial research, practice, teaching and writing – guided by the question how this ambiguous notion can be productively subverted, challenged and reclaimed from various artistic perspectives.

In light of the recent and ongoing funding cuts in Berlin and their politically motivated dimension, the importance of this question is becoming increasingly evident. From 2024-2025, soft power’s basic operational costs are funded by the Berlin Senate – beyond this, we apply for funding for each of our projects, as one of our objectives remains to pay everyone involved for their labour, artistic or otherwise. As a non-profit organisation, we have so far depended almost entirely on public funding structures, which in Germany have long been cherished for their supposed independence from political positioning. In the current political landscape, more than ever we must understand that this is shifting, and find ways to circumnavigate, or undermine, these structures – which is indeed something that we critically, sometimes ironically, allude to with our name, soft power – the name in its intentional ambiguity has certainly come to hold different meanings for us as we go through a process of self-instituting. If anything, the situation encourages us to be more resourceful as we attempt to build an alternative institutional model, and to keep enabling pluralistic discourse.

What was the first exhibition at "soft power", and how have you evolved since then?

EH: The building that we, along with around 40 artist studios, have had our space in since late 2020 – and which soft power will in fact leave towards the end of the year – is the former factory building of the chocolate company Sarotti in Berlin-Tempelhof. This is where Sarotti created one of the most famous German trademarks in 1918: A racist depiction of a Black person, designed in the spirit of the advertising strategies of the late colonial era. As an architectural representation of power and a colonial and neo-colonial self-conception, for our very first project Goodbye, Sarotti, the former Sarotti factory became the site for a kind of archaeological interrogation, revisiting the ghosts of its past. We invited artists from the building via an Open Call to collaboratively engage with the building’s history, making continuities of colonial structures visible, locating them in the district and discussing them with our new public. In exchange with Berlin Postkolonial e.V. and Dekoloniale, the aim of this first exhibition (which took place in the courtyard of the factory due to the pandemic) was not only to reevaluate and critically discuss this site’s past, but also to actively shape its future.

As we are set to move out in October 2025, we are closing a chapter here, and we are excited for the future of soft power, even if it is still an uncertain one. Already prior to this pending move, soft power has started to extend beyond the space: we have been invited to teach at art schools, curate exhibitions in other locations (like our exhibition with Selin Davasse wich opened in June 2025 at Mouches Volantes in Cologne), and we will take part in Rupert’s residency and education programme in Vilnius later this year, to name a few examples. Beyond being a physical venue, soft power has increasingly become a conversation, not just between the two of us as its artistic directors, but also with the community that has formed around it.

How did the exhibition "Changing Room" come about? What concept is behind the show?

LB: As mentioned, Eva and I are interested in opening up this conversation to others beyond our work as a duo. Last year, we invited French curator Clémentine Proby to develop a project together, and the group exhibition Changing Room which opened in May 2025 was the result of this collaboration between friends. The exhibition engaged with the teenage bedroom as a mental and physical space – one where our social and political beings have taken shape, conforming to our environment, or rather, rebelling against it. We were interested in revisiting this time-space from a perspective that highlights this oftentimes painful moment of transformation. So, the title Changing Room, of course, also conjures the rituals of shopping and its gendered connotations: watching yourself in the mirror, examining your transforming body like a monster, and coming to terms with your self-image. We considered the teenage bedroom in a similar way: a space to try things on, to look at oneself, to assess and transform; a space for trials, errors, identity rehearsals. While teenagers often give form to their world and their culture in a radical manner, paradoxically, their urge to stand out is often accompanied by a strong desire to “fit in”. The exhibition reflected on this space where the self is produced between longing expectations and the reality of life; between what and whom we assimilate to and the ideals we nurture. We asked ourselves: Which of the dreams we once had of who we wanted to become have ever materialised outside these four walls?

How did you go about inviting artists for "Changing Room"?

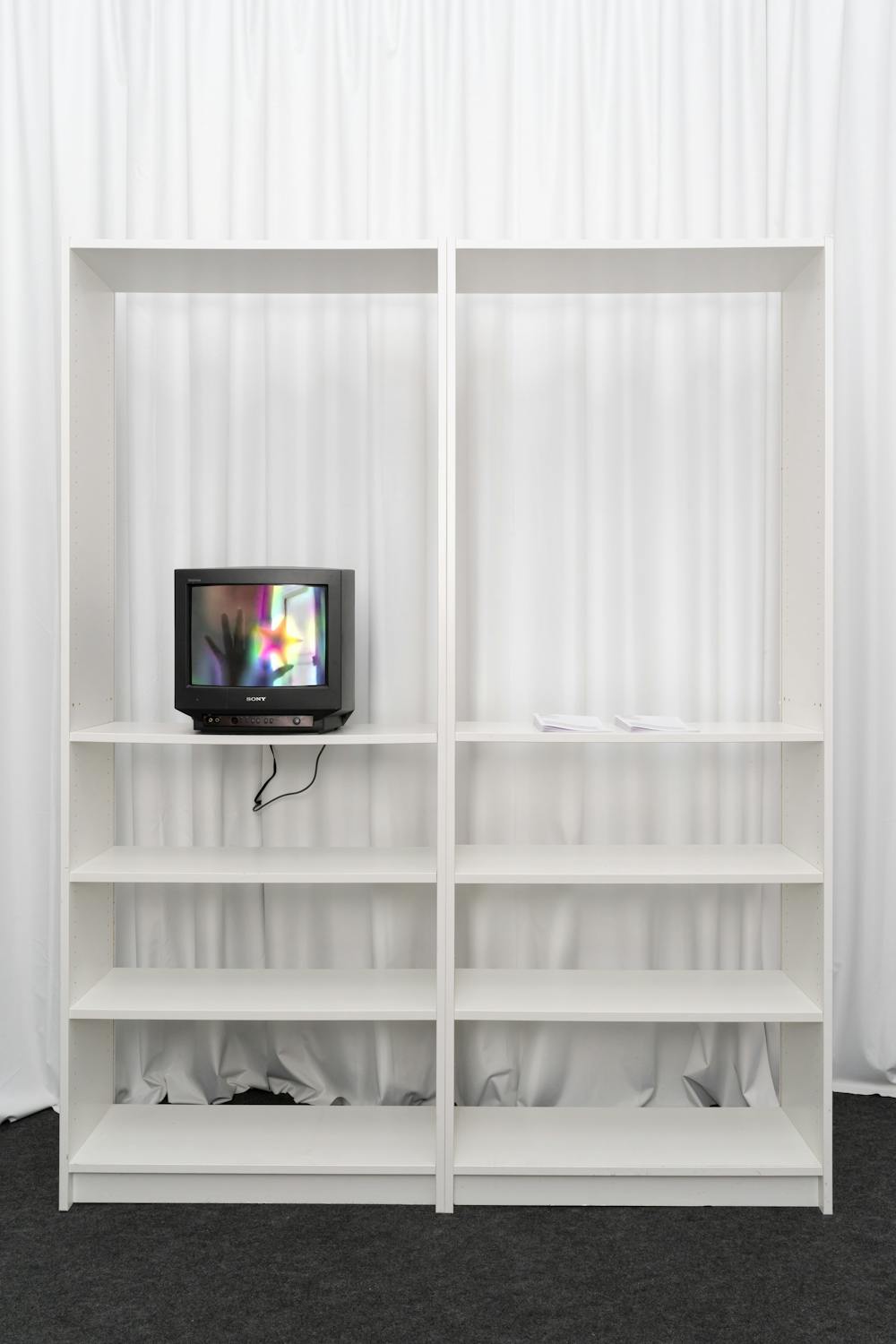

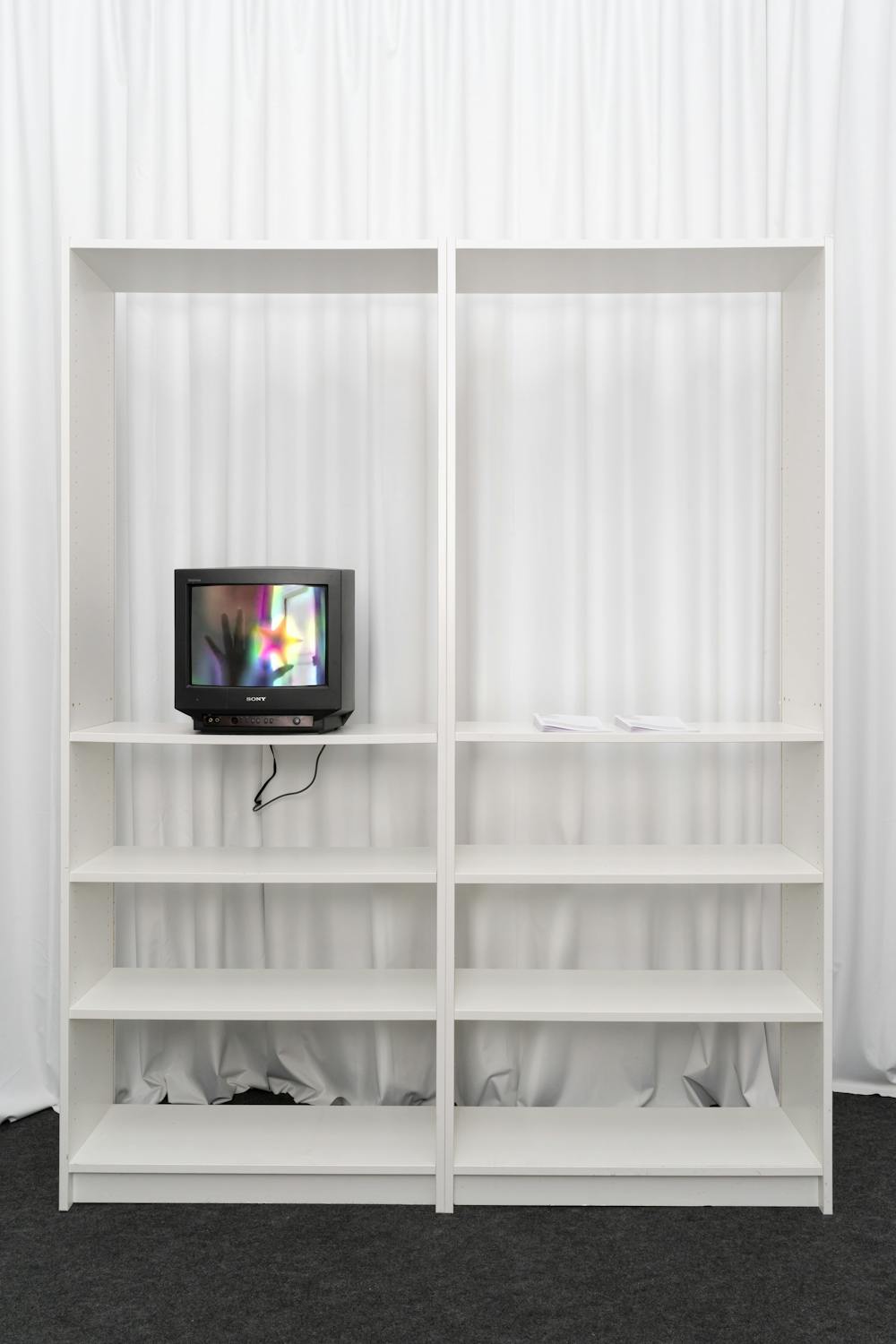

LB: In our initial discussions with Clémentine, we spoke a lot about the question whether there is such a thing as a “universal” teenage experience across generations and geographies. So, we were really excited to work with a group of artists of different age groups (born between 1978 and 2001), who brought in their individual perspectives. At the same time, their contributions produced really interesting overlaps, both thematically and aesthetically. The exhibition design aimed to critically reflect on these overlaps by recreating a domestic setting familiar to many with IKEA’s ubiquitous “Billy” furniture.The shelves structuring the exhibition acted like standardised altars for small objects, personal souvenirs and idols, meticulously kept and cherished. Like social media (Tumblr then and TikTok today), they offered a grid to bring those life fragments together into an ordered mosaic, produced with a sense of urgency and DIY.

What were themes that resonated across different works?

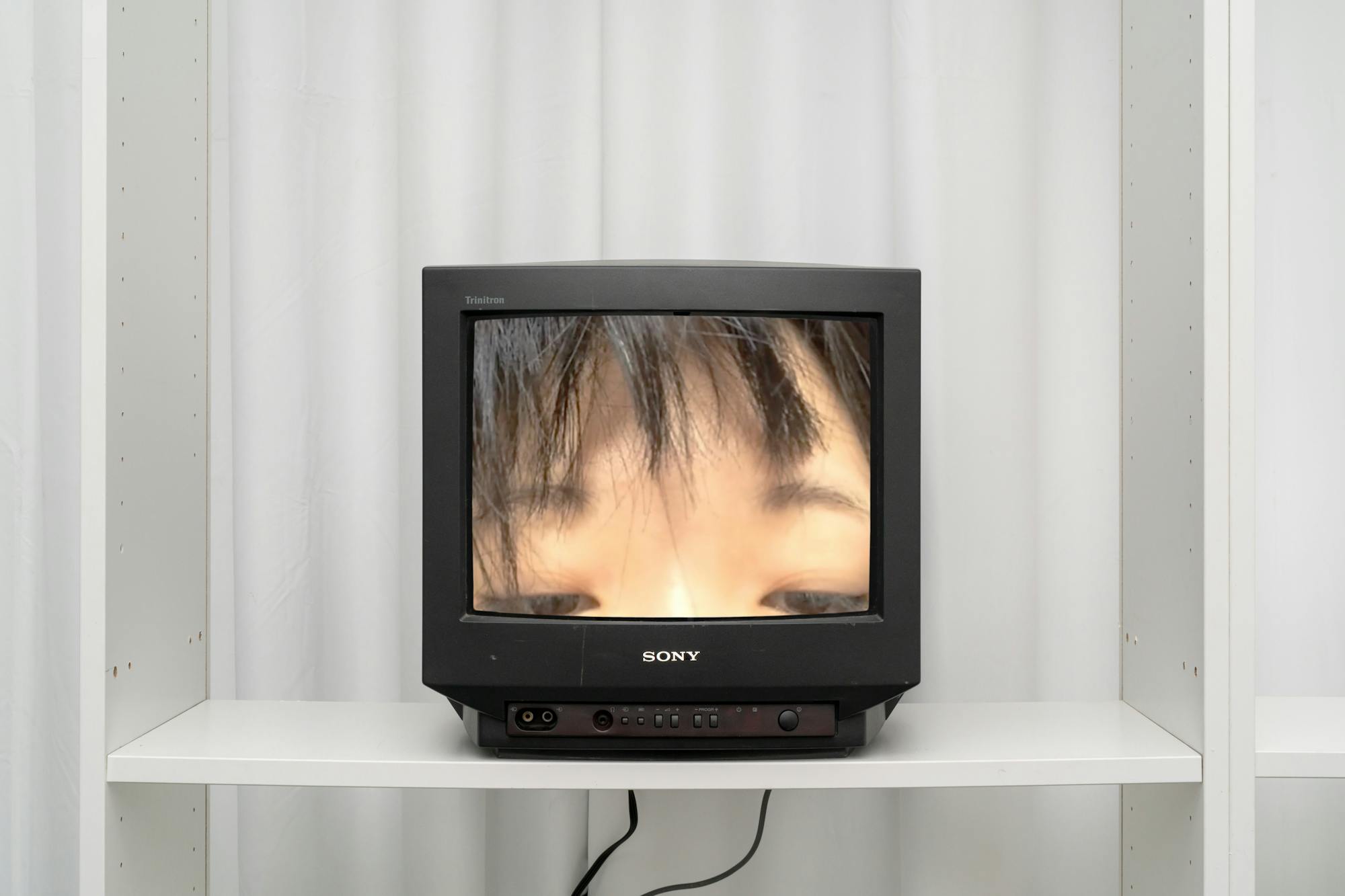

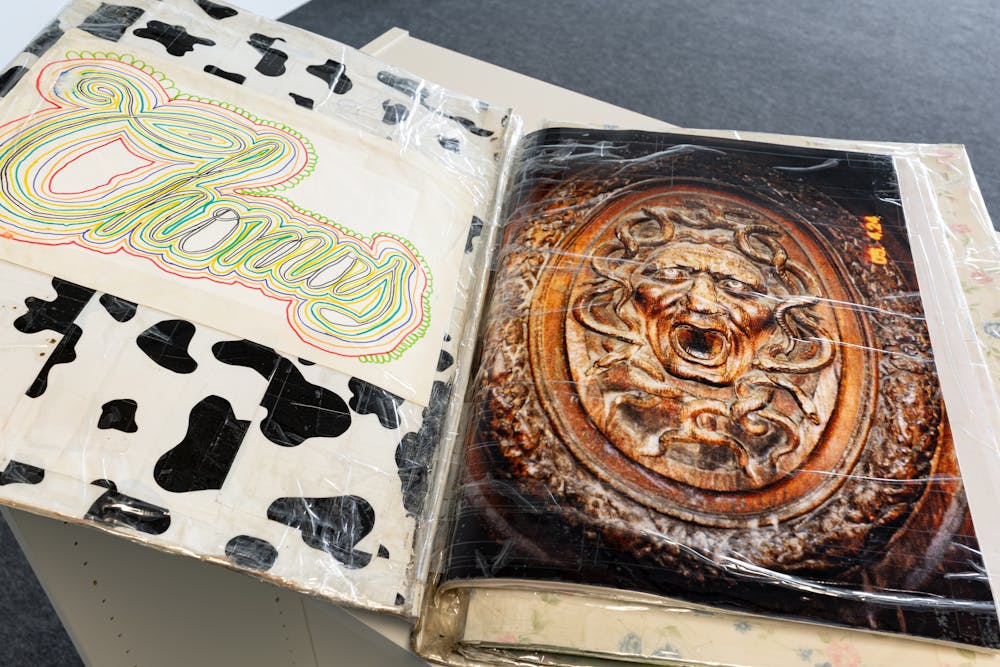

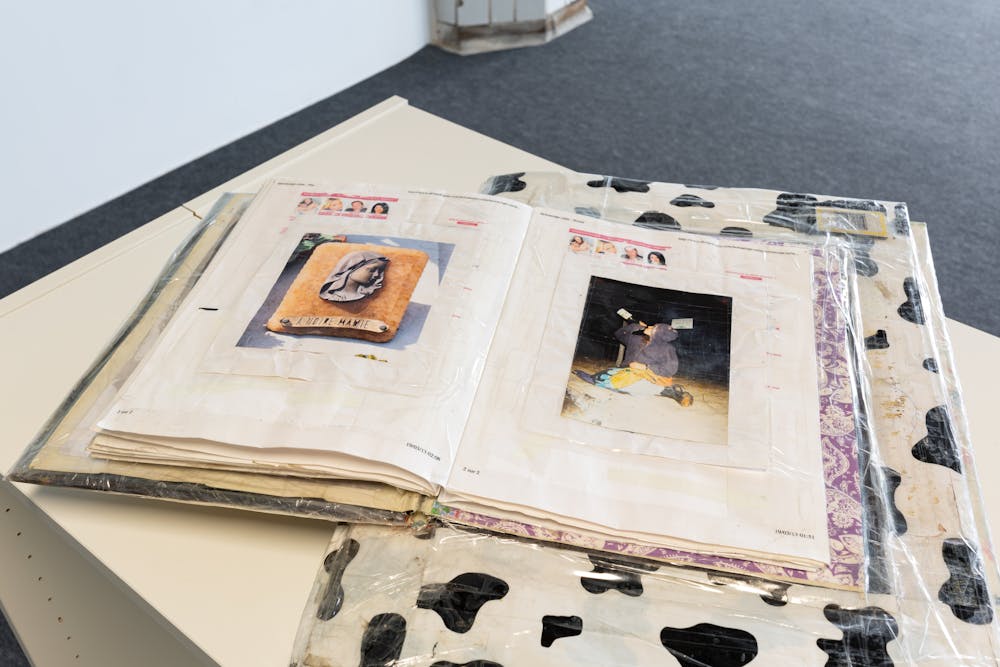

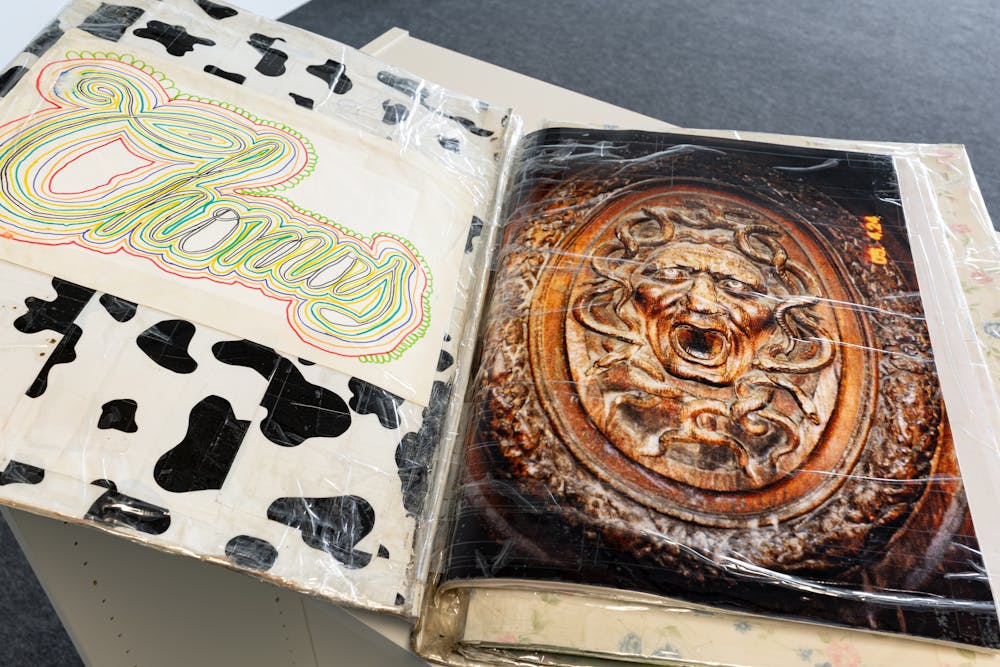

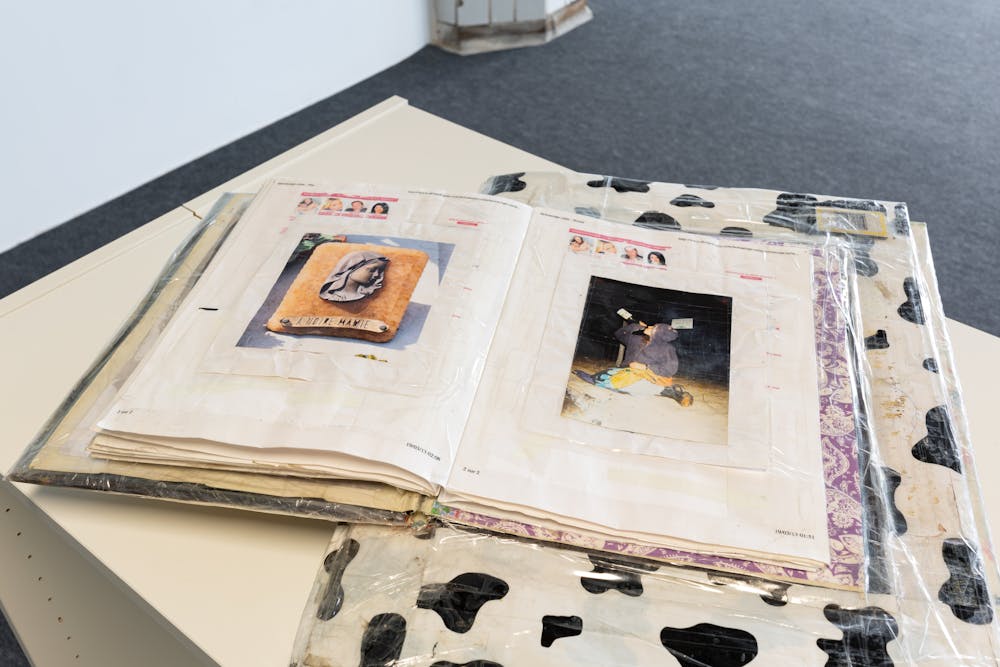

The trio of works by the collective Kim Petras Paintings, who engaged with fandom and the quasi-spiritual attachment to objects and rituals, as well as Thomas Cap de Ville’s handcrafted books drew from this impulse. Mapping his experiences along the uncertain and haunted path towards adulthood, Thomas has accumulated photographs, flyers, fragments since the late 80s and assembles them with scissors and clear tape into books that carry a heavy, almost religious aura. Like Thomas’ books, many of the works in the show echoed the rebellious tone and attitude of adolescent life, for example Maggie Lee’s diaristic film collages, which evoke camcorder home videos as much as they resonate with a present documented and shared in snippets on social media. In a similar fashion, Anaïs Fontanges hoards images from advertising, pop culture, dreams, thoughts, and emotions, which she reshuffles into colourful and expressive drawings. Herself and her own body recur as the main subject of her work, shaped by but also resisting society’s toxic and normative projections of femininity. Equally reflecting on this moment of formation as a state of vulnerability, Ash Love’s hanging sculpture made from a discarded bedframe conveyed a feeling of innocence and the need to be reassured; the attempt to create a safe and enveloping space. The dreamstate was very present, also through Marius Meyer-Jens’ series of paintings of teeth: a recurring dream, and indeed a recurring motif throughout the exhibition. While these close-up image sections of teeth reminded some visitors of the experience of being sent to the orthodontist for a painfully self-conscious period of puberty, dreams involving teeth are said to often symbolize change and personal growth as well as feelings of loss and transience. This in-betweenness that characterizes teenagehood – still innocent and child-like yet haunted by the standardisation and normativity requested by adulthood – seemed to be strangely embodied by Arash Nassiri’s ghostly, monochrome grey doll houses. Beyond the childish desire to play “dream house”, in their recontextualisation, they evoked a sense of austere melancholy. We wanted to show that this room is both a space of daydreams and of nightmares.

In 2023, we inaugurated a project called "Utopian Library" with a bookshelf sculpture by artist Charlotte Duale. A utopian library, in our understanding, should serve both as a library of utopias, but also as a utopian library, a library under utopian auspices. What book would you like to see added to our library?

LB: One book that immediately came to our minds, because we have recently been reading and discussing it together, is Charlotte Beradt’s The Third Reich of Dreams published in 1968. This text was brought to our attention by Fynn Ribbeck, an artist whom I’ve recently had the honor of writing a catalogue essay about and who refers to Beradt’s book in his absolutely fascinating and rather dystopian video works (thanks again to Fynn!).

Charlotte Beradt was a German Jewish journalist and publicist, who under the Nazi regime was banned from working and started to write down the dreams of her Berlin friends and neighbours between 1933 and 1939. She collected the dreams of “normal citizens” and gradually smuggled them out of the country, from which she finally fled in 1939. Fifty of these dreams were later published in an anthology that uniquely illustrates how terror is internalised even in the most private of spheres and how propaganda colonises the imagination even in sleep. Beradt’s collection does not tell a story of resistance. Rather, she illustrated how the fear of total surveillance formulated in the subconscious and the loss of a private existence, which Hannah Arendt would later describe as the fundamental phenomenon of totalitarian rule, led the large majority of Germans to “come to terms” with the situation in Nazi Germany and stay silent about it; the book tells the timely story of how creeping adaptation, preemptive obedience and self-censorship culminated in total apathy.

What makes Beradt's book a candidate for a utopian library?

EH: Of course, the book does not describe a utopia, quite the opposite. Charlotte Beradt never necessarily regarded dreams as realistic representations of reality or history; rather, her text seems to point to the political and ethical agency of the dreamer. In light of current political developments – repressive, authoritarian, and discriminatory tendencies that, with the support of the media, are being realized not only on the growing right-wing fringe but also in the center of society – this book urgently appeals to our individual capacity to become active, to be vigilant, and awake. Therein lies the immediate relevance and perhaps also the utopian potential of this book. When I went to buy it, I was happy to hear the bookseller say that after years of being relatively overlooked, recently, a lot more people had been asking for it. That being said, we would love for it to be included in your library.

The exhibition "Changing Room" at soft power co-curated with Clémentine Proby, which ran throughout May 2025, was supported by Kemmler Foundation.

Installation view: Changing Room, co-curated by Clémentine Proby and soft power, Berlin, 2025. Photo: Eric Bell.